Lately I’ve been trying to learn more about Bash and command-line tools like curl and jq. It’s just fiddling around, but it’s fun and surprisingly addictive.

A few recent mini-projects:

You can’t spell “Toronto City Council” without “TTY”

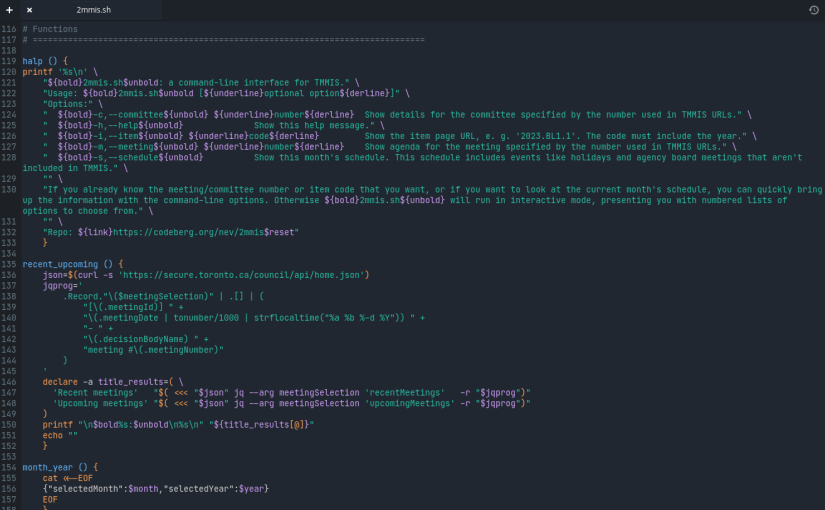

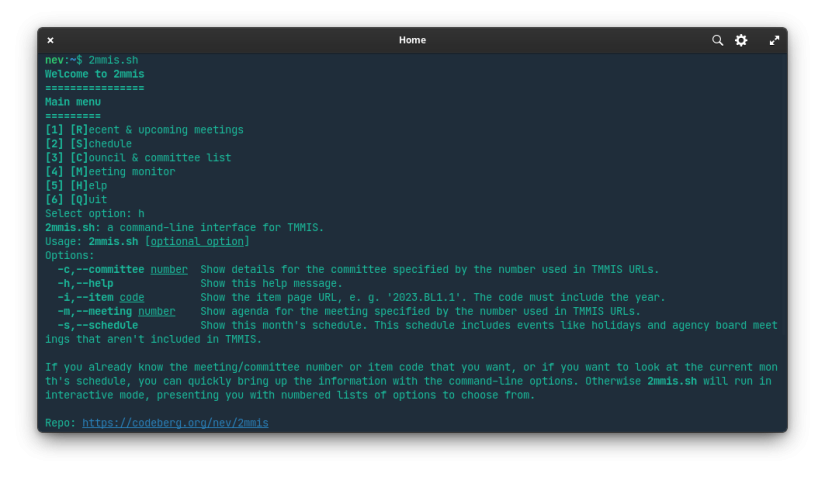

2mmis is a command-line interface for TMMIS, the Toronto City Council Meeting Management Information System. They revamped the site earlier this year; the front end still isn’t terribly impressive, but on the back end, they’ve implemented an (apparently undocumented) API that serves data in JSON format.

At first I thought about using it to generate simple static web pages with meeting and agenda data, but it was less complicated to make something completely terminal-based. It can show you monthly schedules, committee information, meeting agendas, and more. It’s just curl, jq, and a lot of printf statements, basically.

Party like it’s 1199

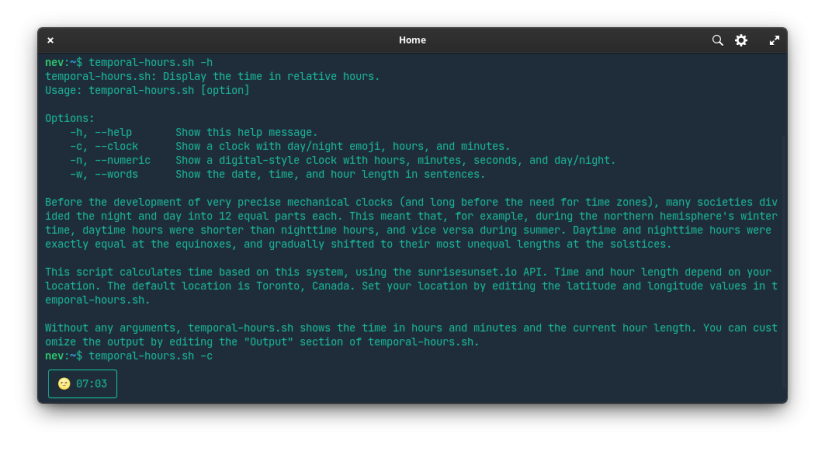

Recently, with the clocks “falling back”, there was a lot of the usual Discourse on fedi (as I’m sure there was on other social media) about Daylight Savings Time and what would be better, and I felt compelled to remind people of how they did it in medieval Europe (among other premodern societies): the night and day were each divided into twelve hours, no matter how long they were. This meant that in more northerly latitudes, during the winter nighttime hours would be longer than daytime hours, and vice versa during summer.

It’s obviously completely unfeasible in this age of time zones and rapid travel, but just for kicks, temporal-hours.sh calculates the hour according to this system based on your geographic location. It uses jq and the SunriseSunset.io API to find sunrise and sunset times for your location, then just calculates the length of the night and day and divides each by 12. You can turn it into a little clock running in your terminal by calling it with watch, and be on medieval time all the time.

“Hacking” Metazooa

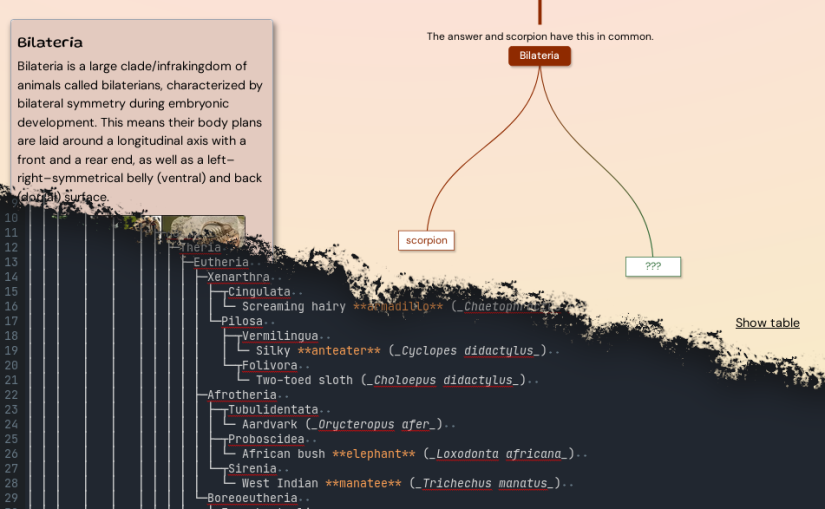

Metazooa is a fun Wordle-style guessing game where you try to narrow down the mystery animal based on its phylogenetic relationship to the species you guessed. My only gripe is that the set list of species you can choose from is very biased towards mammals and vertebrates in general. Like, there’s three species of Equus alone (horses, zebras, and donkeys), but only four species of arachnids!

I tried looking at the various scripts to see how it worked, but they’re all heavily obfuscated. However, a list of all the common names you can guess, plus the scientific name of the mystery animal, is right there in the web page’s source code when you load a new game! So I put together this script which uses curl, grep and sort to load thousands of Metazooa practice games, grab each mystery animal’s name, and delete the dupes to produce a list of all the possible species. Then I plugged it into NCBI’s Common Tree generator to produce the complete phylogenetic tree. The repo also includes the complete list of common names and the scientific names they correspond to.

I’m just a beginner at this, so the code is not that good. If you see room for improvement or want to offer some helpful hints, leave a comment—or make a pull request or issue on Codeberg!