Back in May I recapped the arachnid highlights of the year to date. Since then I’ve found some species I had no idea occurred here, and seen some things in real life that I’d only ever read about! Here’s my personal top 10 arachnid observations from the rest of 2024.

Phoretic Uropodina on hister beetle

June 6, 2024. iNaturalist.

Looking at the forest of threadlike stalks sprouting from this clown beetle (family Histeridae), your first thought might be that it was infected with some kind of entomopathogenic fungus. But if there’s anything I’ve learned from years of looking at bugs: it’s never lupus Cordyceps.1

Until now I’d only heard of uropodine mites riding on other arthropods stuck tight to the surface. But some Uropodina exude anal pedicels (what a fun phrase) that are long and thin! This figure from a paper about phoresy in Uropodina has (much better) photos of what that looks like up close.

Gravid Synemosyna formica at the Oculus

June 8, 2024. iNaturalist.

I’d spotted a few Synemosyna formica ant-mimic jumping spiders at the Oculus before. But this one was so gravid (pregnant with eggs) that her abdomen practically looked like a lightbulb!

Gea heptagon couple near the Oculus

June 8, 2024. ♀, iNaturalist; ♂, iNaturalist.

During the same excursion to the Oculus, I wandered a little further down the Humber trail to a marshy meadow by a creek. In the long, triangular-sided grasses there I found a most unusual pair of orbweavers with angular, pointy, ornately patterned abdomens. They were a species I’d never seen before, the appropriately named Gea heptagon. Southern Ontario seems to be near the northern edge of their range in eastern North America.

Tetragnatha making egg sac, depositing and loading sperm

June 17, 2024. ♀, iNaturalist.

For years I’d been seeing a particular kind of spider egg sac in the deep grooves of large willow trees: a tufted sac suspended at the juncture of three taut silk lines. One night, down among the big willows by the Palais Royale, I saw a large female long-jawed orbweaver (Tetragnatha) going back and forth reinforcing a similar three-line structure. Could it be…? I stayed and watched for ages as she wove a soft little pocket where the lines met, pressed her abdomen to it and exuded a wet clump of eggs, covered the whole bundle in layers of silk, and went over it again and again, bobbing her abdomen, to create that familiar tufted texture.

Like practically all arachnids,2 spiders do not have aedeagi or penises. In spiders, the male exudes a bit of sperm from his genital opening, which is on the underside of his abdomen, and then draws it up into the complex organs in his pedipalps. During mating, he inserts a pedipalp into the female’s corresponding genital opening (which is, like his, on the underside of the abdomen) and pushes the sperm out, a little like using a turkey baster. (Both pedipalp and genital opening are uniquely convoluted, like a key and a lock, and can be used to definitively identify a spider’s species.)

I’ve described this many times, but this night was the first time I actually saw it happening! I wasn’t quite sure what I was seeing at first. As you can see, unlike the “sperm webs” of tarantulas, there isn’t anything particularly special about the web; it’s just a bit of silk. It also didn’t take very long. I feel extraordinarily lucky to have seen it.

Tetragnatha viridis by the tracks

July 24, 2024. iNaturalist.

The Tetragnatha I’ve seen so far have all been generally silvery, gold (sometimes with a reddish tinge), or white and brown. Pretty up close, but not especially striking from a distance. But this little spider, hanging upside-down from a small orb web among the vines on the chain-link fence above the tracks, was a bright green! Once again, I’d seen pictures and illustrations of Tetragnatha viridis, but having never encountered one so far, didn’t expect to find one in person. Especially along a stretch of path that I often walked and whose variety of spiders I am pretty familiar with. But I don’t think there’s anything else it could be.

The spider’s size and the position of the orb web made it difficult to get good pictures. I returned two days later hoping to find it again, only to see that the City had razed and hauled away all the vines and shrubs along the fence—including my rare find, so far the only one in the old City of Toronto.

Pelegrina in tansy heads

August 8, 2024. iNaturalist; August 23, 2024. iNaturalist.

Sometimes the breakthrough is more about learning where to find particular spiders. Once you know their preferred habitats, it becomes easy to find them again. This summer I learned that the broad bouquets of bright yellow tansy (Tanacetum) flowers are an ideal place to find the adorable, ornately patterned Pelegrina jumping spiders, which until now had been a rare find for me.

In summer many of the paths through city’s wilder areas are virtually lined with tansy (look for the fern-like foliage), and you can stop and look under every single one. No one’s going to stop you. Even after the tansy is done blooming, look for jumping spider retreats—sacs of thick, soft, opaque silk, with a slit-like entrance—under the dense canopy of the dead seed heads.

Cyclops P. audax by the Sunnyside pool

August 27, 2024. iNaturalist.

It had been many, many years since I last found any bold jumping spiders (Phidippus audax) living in the holes of the metal railing that runs along the asphalt path between the Sunnyside pool and the lake. This year, though, there were so many! I felt positively blessed.

These little cuties lived just inside the holes (about 1 cm across), and would often hang halfway out, looking around curiously with their big, round eyes, and with a little care you could get great photos. I was taking pictures of one when I realized one of its primary eyes was entirely missing! There was just a hairless, sunken patch where the eye should be. Again, I’d seen photos of spiders with similar eye abnormalities, but never expected to see it in person.

I named this jumper Polyphemos, after the Cyclops in the Odyssey (having been re-reading Emily Wilson’s recent translation earlier this year).3 It had gotten surprisingly big for a spider with such a handicap. I saw it a few more times that summer.

Eratigena agrestis in the Sunnyside willows

October 10, 2024. iNaturalist, iNaturalist.

When fall comes, I make sure to always keep an electric toothbrush in my bag; it’s dead handy for luring funnel-weavers (family Agelenidae) out onto their webs from their funnel-shaped retreats. For some time I’d been aware that the ones living in the big old willows just past the Sunnyside pavilion were not quite like the Agelenopsis I saw everywhere else. For one, it was normally a little odd to see Agelenopsis so high up in trees. There was also something different about the patterns on their backs.

I’m hopeless with other agelenid genera, so I was thrilled to see iNat regular jeremyhussell identify these spiders as Eratigena agrestis, a. k. a. hobo spiders. This species is native to Europe and was introduced to the Pacific Northwest ages ago, and there are only a few scattered populations elsewhere. Apparently one of those populations lives around the Golden Horseshoe!

This spider has long been maligned as dangerously venomous,4 but its bad reputation is entirely unfounded. For more on this, see Travis McEnery’s excellent video.

Mesostig on blister beetle, High Park

November 5, 2024. iNaturalist.

The day of the US election I resolved to stay offline as much as possible. I was out on Hawk Hill in High Park, taking pictures of the many huge, showy blue-black oil beetles (Meloe) eagerly eating grass and other soft green plants in the undergrowth. Then I headed down to Grenadier Café to relax with tea and cake. I was looking over my photos when I saw that one of them, the first one I’d found that day, seemed to have something under its chin. Oh my god, a mesostigmatid mite!

Afterwards I headed right back up the hill again to see if I could find the same beetle. I did (they are not very fast-moving), and managed to get some closer pictures! I was very careful not to touch it; Meloe, like other beetles in the blister beetle family, can defend themselves by exuding cantharidin, an oily compound that causes chemical burns. Luckily the beetle was quite placid and not concerned with anything but eating. It even walked onto my hand of its own will, but since it was not alarmed, I was perfectly fine.

Later, I found a similar observation on BugGuide from 2005. Phoresy? Accident? Who knows?

Acaridae mating, my kitchen

10 seconds of mite sex.

November 16, 2024, November 28, 2024.

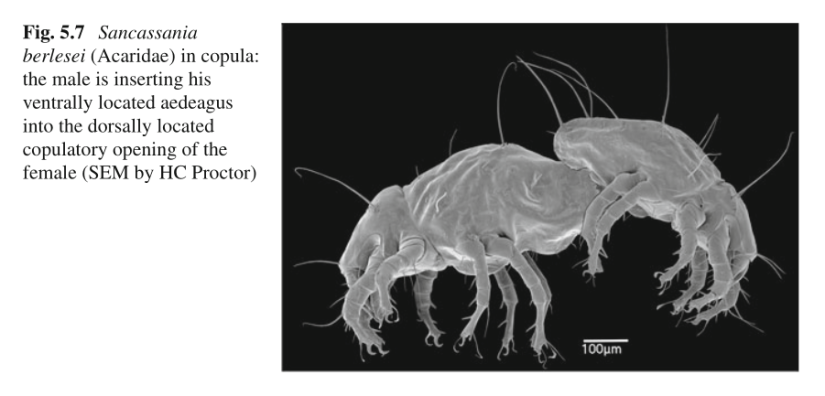

D. E. Walter and Heather Proctor, in their wonderful Mites: Ecology, Evolution & Behaviour, explain, “Mites have a bewildering diversity of sperm transfer methods. In males, every appendage that can be modified for reproduction has been.”5 Earlier I mentioned that most arachnids don’t have aedeagi/penises. Mites in the lineage Astigmata are one of the exceptions, because mites have an exception to everything (nature abhors a vacuum, and apparently chooses to fill that vacuum with mites. Some of which have penises). There is a figure in the book showing a mating pair of astigs—yes, the female has a secondary genital opening on her back:

Anyway, I had been keeping a fruit fly (Drosophila hydei) culture going, because although I did not have a pet spider at the time, multiple times in the past I have ended up needing to feed some arthropod and it’s, like, Christmas Eve and I can’t just get one outside and the nearest place that has them is across town, or whatever. Anyway, their deli cup6 experienced an explosion of astigmatid mites, the kind that are sometimes called “flour mites”, “cheese mites”, “grain mites”, etc.—small white mites, generally some species in the family Acaridae, that are commonly found in high numbers feeding on and inhabiting stored food.

On one hand, I needed to give them a new deli cup. On the other hand, it was winter and you need to work with what you’ve got! So I kept the old tub around a little longer to observe the mites, and recorded the video you see above.

Like I said in the last spider post, 2024 marks about 10 years of spidering for me. I’m still finding new things all the time. 2025 is no doubt going to be a giant trash fire, but at least the arachnid world will keep finding new ways to delight me.

- Mostly because the one you’re thinking of got reclassified as Ophiocordyceps. ↩

- The exceptions are the order Opiliones (harvesters) and certain mites (we’ll get to those). ↩

-

I really, really like it. Here’s a New York Times article (archive) about it. Wilson’s translation is plain, direct, and compact (she aimed to keep to the exact same line count), written in iambic pentameter that positively carries you along on a current when you read it out loud.

One of my favourite passages, which I always flip to in any translation, is the bit where, on the isle of Phaiakia, Odysseus hears the poet Demodokos sing the story of the Trojan Horse:

Odysseus was melting into tears;

his cheeks were wet with weeping, as a woman

weeps, as she falls to wrap her arms around

her husband, fallen fighting for his home

and children. She is watching as he gasps

and dies. She shrieks, a high clear wail, collapsing

upon his corpse. The men are right behind.

They hit her shoulders with their spears and lead her

to slavery, hard labor, and a life

of pain. Her face is marked with her despair.

In that same desperate way, Odysseus

was crying… - In North America, that is. That it has lived for aeons in Europe without any reports of medical significance is just one clue that its dangerousness is urban legend, not fact. ↩

- Walter, D. E., & Proctor, H. C. (2013). Mites: Ecology, Evolution & Behaviour, 2nd ed., p. 60. Springer Netherlands. DOI: 10.1007/978-94-007-7164-2 (Sci-Hub [PDF]) ↩

- Fruit flies sold as feeder insects for amphibian, reptile, and arthropod pets are typically kept in those 32 oz. clear plastic tubs used in grocery stores and the like. At the bottom is a layer of edible paste, mostly starch (e. g. powdered potato), sugar, and yeast. It is filled with excelsior (wood wool), kind of like that straw or crinkly shredded paper used in Easter baskets and the like, but made of very thinly sliced wood, for them to crawl on (though one could use anything similar). The lid has small air holes, or large ones covered by coffee filter-like paper, so they can’t get out. ↩